www.handicraftsonlinestore.com

https://www.facebook.com/persispersianhandicrafts

http://handicraftsonlinestore.com/google.com/+Persiscraftspersianhandicrafts

In rural areas traditional crafts remained more resistant to European tastes until well into the 20th century (see, e.g., Keddie). Craft work among the village and pastoralist populations of Persia is known mainly from contemporary ethnographic observation and description, as well as from ethnoarcheological studies, especially since the late 1960s (see, e.g., Digard; Black-Michaud, 1986; idem, 1989). Related studies have been focused on settled rural populations (e.g., Kramer, 1977; idem, 1982; Spooner, on the Baluch; Spooner and Mann for wool and cotton production in the Tūrān basin in northeastern Persia).

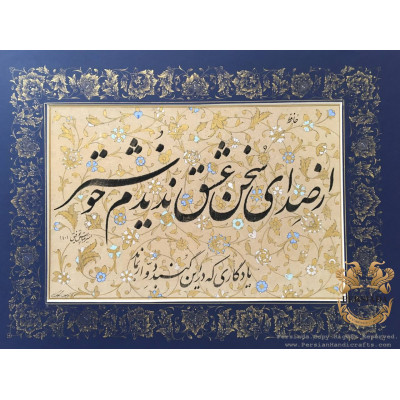

In the 1930s Reżā Shah Pahlavī (1304-20 Š./1925-41), in an attempt to preserve and encourage local production of textiles and other handwork, established schools for traditional crafts in major cities throughout Persia, including the Madrasa-ye ṣaṇʿatī-e Īrān wa Almān in Tehran. The emphasis on tradition received a new impetus in the 1960s, when foreign-trained Persian art students began to return home and consciously sought to revive some of the styles and techniques of the past. At first the tendency was to copy older models closely, but eventually a more creative approach to tradition produced modern solutions.

In Tehran handicrafts were promoted commercially in a number of markets, including connoisseurs of traditional skills, tourists, ordinary household purchasers, and foreign importers. A major exhibition of Persian craft products, including common saddlebags, rough-textured bath mitts (kīsa-ye ḥammām), fleece-lined mantles (pūstīn) ornamented with embroidery, pottery, glass, beehive covers and batik from Tabrīz, Baluch and other needlework, and the like, at the Wakayama castle museum in Japan in 1963 received considerable publicity in Persia, which helped to create a favorable atmosphere in which Farangīs Yagānegī was able, with government support, to establish a handicrafts organization (Sāzmān-e ṣanāyeʿ-e dastī) and an associated emporium in Tehran (Markaz-e ṣanāyeʿ-e dastī; Gluck and Gluck, pp. 24-28). The latter opened in 1345 Š./1966, carrying predominantly purchases made by Moḥammad Narāqī in all parts of Persia, as well as products specially ordered in Tehran and Isfahan by Mehdī and Violette Ebrāhīmīān. Narāqī followed a policy of encouraging artisans to raise their initial cost bids, in order to elicit the best possible workmanship; unfortunately, after his death purchasing for the organization became bureaucratized, and cost-consciousness came to prevail over salability.

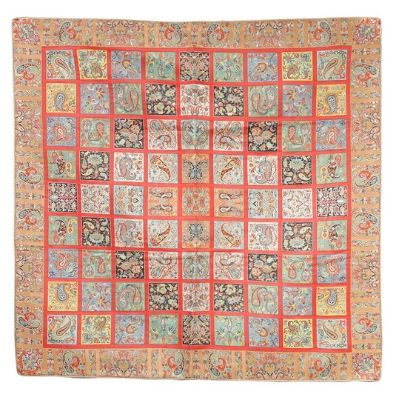

Courtly patronage played an important role in this revival. For example, in 1354 Š./1975 Queen Faraḥ instituted an award for excellence in handicrafts and helped to promote indigenous crafts by appearing in public wearing Persian-made textiles and accessories. Progress was not equal on all fronts, however. Production ofqalamkārs (woodblock-printed cotton tablecloths, curtains, and bedspreads), perennial favorites in the Isfahan bāzār since the 19th century (Plate XII), when they were also exported in quantity (see čīt), was saved from extinction after World War II by foreign buyers. In the 1970s, however, it was curtailed by the Persian handicrafts organization for ecological reasons, as setting colors by rinsing the cloth in the river pollutes the water. A well-meaning attempt to “standardize production” led to enforced use of heavy chemical dyes with the consistency of automobile enamel and virtually destroyed the market. Another problem area was carpets, which for several decades had been a major source of foreign exchange. In the summer of 1345 Š./1966 a chartered plane carrying German carpet dealers visited Persia to persuade those controlling the industry to abandon cheap, garish chemical dyes in favor of natural dyes; to stop attempts to compete with cheap European machine-made rugs; and to concentrate instead on quality despite high production costs, trusting to the connoisseurs’ market to provide sufficient returns. The producers remained unconvinced, however.

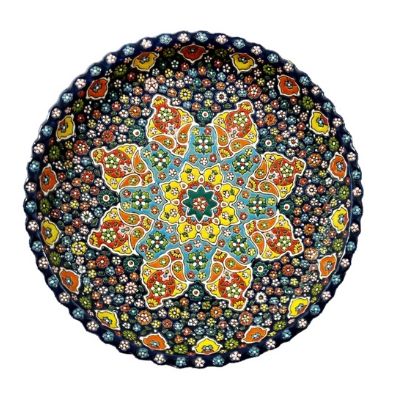

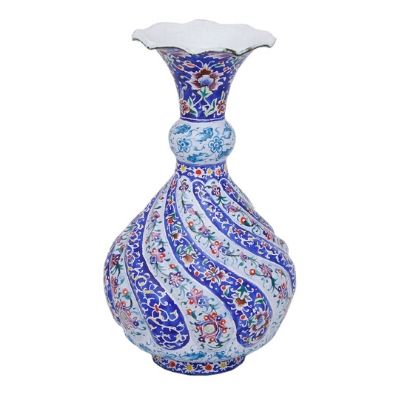

After the Islamic Revolution of 1357 Š./1978 the government banned export of handicrafts and even carpets as part of a general policy designed to control the flight of wealth from the country. Although in the mid-1980s limited exports of carpets to Europe and Japan were allowed as barter for restricted imports, full legal exports based on bank transfers at market exchange rates were resumed only in 1369 Š./1990; in that year 70 percent of the income from carpet exports to Japan was from silk carpets, mostly made in Qom. The quality of workmanship and design in that city has risen in response to Japanese demand for fine workmanship, classic designs, and signed pieces. Qom designs, including the signatures, are also imitated in inferior work from Marāḡa in Azerbaijan. There is considerable foreign demand for tapestry-woven kilims (gelīms), which are now produced for the market in designs incorporating mixed elements from different regional traditions. Other significant exports to Japan are glass and turquoise-glazed ceramics from Isfahan.

On the other hand, limitations on imports, including clothing and cloth, encouraged revival of the qalamkār industry; as antipollution restrictions remained in force, better dyes were developed. Nor did the craft remain limited to tablecloths, curtains, and bedspreads. Japanese television coverage of the Isfahan bāzār in the mid-1980s showed great quantities of cloth and ready-made dresses of “Islamic cut” displayed in the bāzār. The main firm involved in this manufacture is Šerkat-e čītsāz. Large quantities of qalamkārs are currently shipped to Europe and Japan; they include both traditional nonfigurative patterns in three and four colors on heavy cloth tinted with pomegranate skins and newer blue-and-black floral patterns on heavy white cloth.

Nonetheless the departure of many of the most original and highly skilled craftsmen from Persia has caused a serious break in many of the craft traditions of the country. At present the government, largely for economic reasons like creating jobs, is making efforts to restore craft production to prerevolutionary levels, an effort that is also being promoted by private entrepreneurs. Success has been greatest in Tehran, Isfahan, Shiraz, Mašhad, and the province of Gīlān, which is visited by many tourists in the summer. Nevertheless, quality has not so far been a major focus of these efforts.

Continued….

Article Source: iranicaonline.org/articles/crafts-

-400x400.png)

Leave a Comment