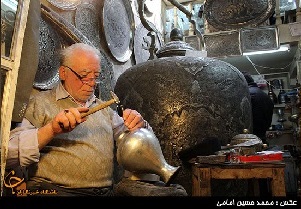

Post: The Art of Persian Metal Work on Brass, Copper & Silver - Part I

Perhaps the most continuous and best-documented artistic medium from Iran in the Islamic period.

Metalwork is perhaps the most continuous and best-documented artistic medium from Iran in the Islamic period. It survives mainly in brass (see BERENJ) and bronze. Most gold and silver wares, better known through literary accounts, were likely melted down (Ward, pp. 10-11). At times, echoing the forms of more ephemeral or less costly materials such as ceramics, metalwork from Iran and adjacent lands served a wide variety of utilitarian functions. These were nonetheless luxury wares that absorbed the creative energy of some of the best artists and reflected the main artistic trends and the tastes of successive dynasties. Written sources are an important means of documenting this medium. In addition to literary works, primarily geographical texts in Arabic and Persian, which provide information on centers of production and sources of metal ores (Allen, 1979, pp. iv-viii), the objects themselves often supply internal documentation through their inscriptions. Iranian metalwork is therefore an important resource for understanding the art Iran in the Islamic period in particular and the history of Islamic art in general.

Early Islamic metalwork. Silver and gold plate, especially the former, provide a well-documented art form in Sasanian Iran and in pre-Islamic western Central Asia. Sasanian silver vessels (bowls, dishes, cups, ewers, and bottles), often decorated with imperial symbolism such as the royal hunt (Harper and Meyers, pp. 40-98), must have appealed to the new Muslim rulers, who sought to emulate the traditions of Persian kingship. This can explain the existence of a large group of mainly silver gilt objects that continue and readapt the Sasanian style. They are often characterized simply as “post-Sasanian,” but the issue of their provenance and dating remains uncertain (Harper, pp. 24-78; ART IN IRAN v. Sasanian, sec. “Silver plate”).

As the new Islamic polity asserted control over Iran and the territories to its east, many of the same metalwork forms and techniques continued to develop and evolve, while much of the representational imagery gradually lost its original meaning. It seems likely that objects fashioned of both silver and gold persisted as status symbols for the new aristocracy. It is therefore often difficult to pinpoint where Sasanian art ends and Islamic art begins in the first centuries of Muslim rule. The situation with contemporary base metal is similar, but these objects also stand more obviously in a definable relationship to Islamic art. For example, a tall, pear-shaped cast bronze ewer, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and set on a high foot with handle in the form of an elongated panther exemplifies the transition from the Late Antique to the early Islamic period (Figure 1). Abstract ornament on the body of the vessel combines vegetal designs with a highly stylized version of the paired wings and central orb of the Sasanian royal crown, while the pattern of overlapping floral petals on the foot and the feline handle hark back to the classicizing influence in Parthian art (Harper, pp. 60, 66). On the other hand, the stylization and abstraction of the decoration and the proliferation of repetitive surface decoration are singular features of Islamic art.

Medieval metalwork. During this period Iranian metalwork underwent considerable modification in terms of technical, iconographic, and aesthetic standards. Although the mechanism for transmission is not always clear, it is apparent that Jaziran (i.e., of Upper Mesopotamia) and Syro-Egyptian metalwork of this period also benefited from as well as contributed to these developments in Iran (Ward, pp. 71-91).

Sometime toward the middle of the 12th century, the metalwork industry in Iran underwent a major transformation that was to be of signal importance for its history. Bronze and brass objects, some of them copying shapes in precious metal, were inlaid with silver and copper or gold. At roughly the same time, hammered brass began to replace cast brass in the manufacture of luxury metal-ware. Khorasan has long been recognized as the center for the production of these wares. Two key pieces whose inscriptions provide evidence for an attribution to Khorasan, and more specifically to the city of Herat, are the so-called “Bobrinski Bucket” dated 559/1163, in the Hermitage, St. Petersburg (no. CA-12678), and a faceted ewer of 577/1181-82, in the State Museum of Georgia, Tbilisi (Kana’an, pp. 198-201; Ward, p. 77). There is also a reference in Qazvini’s late 13th-century geographical treatise indicating that Herat was renowned for its brass vessels inlaid with silver (Qazvini, p. 481). Other cities in Khorasan such as Nishapur also may have had their own luxury metalwork industries (Allan, 1982a, pp. 22-25). Khorasanian inlaid wares are notable for the wide variety and virtuosity of their shapes: faceted or fluted ewers, candlesticks whose bulging sides are defined by rows of hexagons worked in relief, and circular inkwells (see DAWĀT) surmounted by melon-shaped dome-like covers. Their largely figural decoration is likewise wide-ranging, including scenes of pleasure and pastime, astrological symbols, zoomorphic inscriptions, and plastically rendered figures of animals, especially lions and birds (Ward, p. 78).

This florescence of Iranian metalwork in the 12th and early 13th centuries was part of a larger period of creativity in the so-called decorative arts, one that changed dramatically with the Mongol invasion, which brought to an abrupt end the important metalwork centers in Khorasan. Post-Mongol metalwork, largely attributable to Azerbaijan and Fars, exhibits simpler and less varied shapes. Bowls, deep basins, flat trays, and tall bell-shaped candlesticks predominate. The decoration is largely figural and often closely follows the style of contemporary manuscript illustration, especially in the first half of the 14th century. Some of the figural scenes are as ambitious as contemporary painting (Komaroff, 1994, pp. 11-20). Their inscriptions provide the first extensive evidence of royal patronage of base metalware inlaid with gold and silver (Komaroff and Carboni, eds., pp. 277-80, Cat. nos. 159-66, 169).

Several examples of inlaid brass objects are inscribed with the names of members of the Il-khanid dynasty, the most impressive of which is an unusual composite vessel known as the Nisan Tasi, in the Mevlavi (Mawlawi) Tekke Museum in Konya, of which its basin and support stand bear the name and titles of Abu Saʿid Bahādor Khan (r. 1317-35; Baer, pp. 3-7). These pieces are more closely related to Mamluk metalwork rather than to other contemporaneous objects from Iran, although this does not rule out an attribution to Azerbaijan.

A number of examples of luxury metalwork can be linked to Fars on the basis of their inscriptions, for example a candlestick dateable to ca. 1343-53, in the Museum of Islamic Art, in Doha (Qatar), inscribed with the name and titles of the Injuid ruler Abu Esḥāq (r. 1321-59; Komaroff and Carboni, eds., p. 278, Cat. no. 162; Figure 2). The candlestick carries depictions of the enthroned ruler and his consort in Mongol attire, which have analogues in contemporaneous illustrated manuscripts (Wright, pp. 60-67) suggesting that metalworkers and manuscript illustrators may have shared a common iconographic source in the form of drawings (Komaroff, 2002, pp. 189-91). A bowl in the Hermitage Museum is likewise inscribed to Abu Esḥāq Inju, while an inlaid bucket in the same museum dated 733/1332-33 was made for his father Maḥmud Shah (Gyuzalyan, pp. 175-78; Komaroff and Carboni, ed., p. 278, Cat. no. 161). Based on these and several other related objects, Fars seems to have been an important center for inlaid metalwork. The prominence of figural imagery declined in the second half of the 14th century, giving way to abstract designs inspired by Chinese blue-and-white porcelains (Komaroff, 1992a, pp. 3-4).

Buy Persian Handicrafts at: www.persianhandicrafts.com

Buy Persian Rugs at: www.kimiyacarpet.com.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/persispersianhandicrafts

Google+: https://plus.google.com/+Persiscraftspersianhandicrafts

Twitter: https://twitter.com/persiscrafts

Article Source: Click Here

Please Join Our Social Networks to Support us:

-400x400.png)

51 Comment(s)

客户评价是衡量加拿大代考机构保密性的重要参考。客户评价反映了机构的服务质量和客户满意度,能够为其他客户选择代考机构提供重要参考。高保密性的代考机构通常会在市场上拥有良好的口碑和客户评价,客户对其信息保护和保密措施给予高度评价。学生在选择代考机构时,应参考其他客户的评价和反馈,了解机构的保密性和服务质量。例如,查看在线评论和评级网站上的客户评价,了解机构的服务体验和客户满意度。此外,学生还可以通过社交媒体和论坛等渠道,与其他客户交流和分享经验,获取更多关于机构保密性的真实信息。通过参考客户评价,学生可以选择那些保密性高、口碑良好的代考机构,确保信息安全和服务质量。

当您寻找专业的作业代写服务时,我们作业汇是您信赖的首选。我们是一支经验丰富的团队,致力于为留学生提供高质量、定制化的作业代写服务。无论您面临何种学科或难度,我们的专业写手都能够为您提供卓越的学术支持,确保您获得满意的成绩。

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/acapulco-gold-strain/" rel="dofollow">Acapulco Gold Strain</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/afghani-strain/" rel="dofollow">Afghani strain</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/ak-47-strain/" rel="dofollow">AK 47 Strain</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/amnesia-haze-strain/" rel="dofollow">Amnesia Haze Strain</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/blue-gelato-strain/" rel="dofollow">Blue Gelato Strain</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/blueberry-muffin-strain/" rel="dofollow">Blueberry Muffin Strain</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/bubblegum-popperz-strain/" rel="dofollow">Bubblegum Popperz Strain</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/chemdawg-strain/" rel="dofollow">Chemdawg Strain</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/diamond-dust-strain/" rel="dofollow">Diamond Dust Strain</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/gary-payton-strain/" rel="dofollow">Gary Payton Strain</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/miracle-alien-cookies-strain/" rel="dofollow">Miracle Alien Cookies Strain</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/og-kush/" rel="dofollow">OG Kush</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/permanent-marker-strain/" rel="dofollow">Permanent Marker Strain</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/zoapscotti-strain/" rel="dofollow">Zoapscotti Strain</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/blueberry-oil/" rel="dofollow">Blueberry Oil</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/co%e2%82%82-extract-oil/" rel="dofollow">CO₂ Extract Oil</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/delta-8-distillate/" rel="dofollow">Delta 8 Distillate</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/d9-distillate/" rel="dofollow">Delta 9 Distillate</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/delta-10-distillate/" rel="dofollow">DELTA-10 Distillate</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/hhc-distillate/" rel="dofollow">HHC Distillate</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/live-resin-oil/" rel="dofollow">Live Resin Oil</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/purple-punch-oil/" rel="dofollow">Purple Punch oil</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/raw-pure-thc-oil/" rel="dofollow">Raw (Pure) THC Oil</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/rick-simpson-oil/" rel="dofollow">Rick Simpson Oil</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/thc-clear-distillate/" rel="dofollow">THC Clear Distillate</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/thc-d9-syrup/" rel="dofollow">THC Delta 9 Syrup</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/star-killer-oil/" rel="dofollow">THC Star Killer Oil</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/thca-distillate/" rel="dofollow">THCA Distillate</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/thcp-distillate-oil/" rel="dofollow">THCP Distillate Oil</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/whole-melt-extracts-2g-disposable/" rel="dofollow">Whole Melt Extracts 2g Disposable</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/tre-house-hhc-live-resin-disposable-vape-pens-2grams/" rel="dofollow">Tre House HHC Live Resin Disposable Vape Pens (2grams)</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/the-wizard-of-terps-1ml-syringe/" rel="dofollow">The Wizard Of Terps 1ml Syringe</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/ruby-carts-disposable-vape-pen/" rel="dofollow">Ruby Carts Disposable Vape Pen</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/potent-disposable/" rel="dofollow">Potent disposable</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/packwoods-x-runtz/" rel="dofollow">Packwoods x Runtz</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/ace-ultra-premium-disposable/" rel="dofollow">Ace Ultra Premium Disposable</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/backpackboyz-carts/" rel="dofollow">Backpackboyz Carts</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/baked-bar-2g-disposable/" rel="dofollow">Baked Bar 2g Disposable</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/burst-2g-disposable-vape/" rel="dofollow">Burst 2g Disposable Vape</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/cali-company-disposable-vape/" rel="dofollow">Cali Company Disposable Vape</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/choice-lab-2g-disposable/" rel="dofollow">Choice Lab 2g Disposable</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/clean-carts-2g-disposable/" rel="dofollow">Clean Carts 2G Disposable</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/cookies-1g-disposable/" rel="dofollow">Cookies 1g Disposable</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/family-high-range/" rel="dofollow">Family High Range</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/favorites-2g-disposable/" rel="dofollow">Favorites 2G Disposable</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/gassed-up-2g-disposable/" rel="dofollow">Gassed Up 2g Disposable</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/jeeter-juice-carts/" rel="dofollow">Jeeter Juice Carts</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/jungle-boys-vape/" rel="dofollow">Jungle Boys Vape</a>

<ahref="https://disposablecartsuk.com/product/seedless-disposable/" rel="dofollow">Seedless Disposable</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/apple-fritter-strain/" rel="dofollow">Apple Fritter Strain</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/biscotti-strain/" rel="dofollow">Biscotti Strain</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/blueberry-zkittlez-strain/" rel="dofollow">Blueberry Strain</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/cheese-kush/" rel="dofollow">Cheese strain</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/gelato-strain/" rel="dofollow">Gelato Strain</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/gg4-strain/" rel="dofollow">GG4 Strain</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/godfather-og-strain/" rel="dofollow">Godfather OG Strain</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/stardawg-strain/" rel="dofollow">Stardawg Strain</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/super-lemon-cherry-strain/" rel="dofollow">Super Lemon Cherry Strain</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/wedding-cake-strain-2/" rel="dofollow">Wedding Cake Strain</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/white-widow-strain/" rel="dofollow">White Widow Strain</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/girl-scout-cookies/" rel="dofollow">Girl Scout Cookies</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/granddaddy-purple-gdp-strain/" rel="dofollow">Granddaddy Purple Strain</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/ice-cream-cake-strain/" rel="dofollow">Ice Cream Cake Strain</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/master-kush/" rel="dofollow">Master Kush</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/northern-lights/" rel="dofollow">Northern Lights strain</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/skywalker-kush/" rel="dofollow">Skywalker Kush</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/watermelon-gelato-strain/" rel="dofollow">Watermelon Gelato Strain</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/zeus-og-strain/" rel="dofollow">Zeus OG Strain</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/amnesia-haze/" rel="dofollow">Amnesia Haze</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/bruce-banner-strain/" rel="dofollow">Bruce Banner Strain</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/durban-poison/" rel="dofollow">Durban Poison</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/guava-weed-strain/" rel="dofollow">Guava Weed Strain</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/maui-wowie-strain/" rel="dofollow">Maui Wowie Strain</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/mimosa-strain/" rel="dofollow">Mimosa Strain</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/sour-diesel-strain/" rel="dofollow">Sour Diesel Strain</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/super-silver-haze/" rel="dofollow">Super Silver Haze</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/big-chief-carts/" rel="dofollow">Big Chief Carts</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/cake-vape-pen/" rel="dofollow">CAKE VAPE PEN</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/cali-company-1g-vapes/" rel="dofollow">Cali Company 1g Vapes</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/dope-disposable-vape-pens/" rel="dofollow">Dope Disposable Vape Pens</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/england-trap-1g-vape/" rel="dofollow">England Trap 1g Vape</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/expensive-sht-vapes/" rel="dofollow">Expensive Sh*t Vapes</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/fryd-vape/" rel="dofollow">FRYD VAPE</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/muha-meds-vape/" rel="dofollow">Muha Meds Vape</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/packman-vape/" rel="dofollow">PACKMAN VAPE</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/packwoods-vape/" rel="dofollow">PACKWOODS VAPE</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/cali-plates-hash/" rel="dofollow">Cali Plates Hash</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/fly-farm-hash/" rel="dofollow">FLY FARM HASH</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/16147/" rel="dofollow">Kilogrammes Farm Hash</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/la-mousse-hash-review/" rel="dofollow">La Mousse Hash</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/lemon-haze-hash/" rel="dofollow">LEMON HAZE HASH</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/static-room-hash/" rel="dofollow">Static Room Hash</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/super-pollen-hash/" rel="dofollow">Super Pollen Hash</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/tangie-hash/" rel="dofollow">TANGIE HASH</a>

<ahref="https://englandtrap.com/product/wazabi-hash/" rel="dofollow">WAZABI HASH</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/alien-og-hash/" rel="dofollow">Alien OG hash</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/cali-plates-hash/" rel="dofollow">Cali Plates Hash</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/fly-farm-hash/" rel="dofollow">FLY FARM HASH</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/kilogrammes-farm-hash/" rel="dofollow">Kilogrammes Farm Hash</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/la-mousse-hash/" rel="dofollow">La Mousse Hash</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/lemon-haze-hash/" rel="dofollow">LEMON HAZE HASH</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/pollen-hash/" rel="dofollow">POLLEN HASH</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/static-room-hash/" rel="dofollow">Static Room Hash</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/tangie-hash/" rel="dofollow">TANGIE HASH</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/wazabi-hash/" rel="dofollow">WAZABI HASH</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/41-unicornz-strain/" rel="dofollow">41 Unicornz Strain</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/apple-fritter-strain/" rel="dofollow">Apple Fritter Strain</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/biscotti-strain/" rel="dofollow">Biscotti Strain</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/blue-gelato-strain/" rel="dofollow">Blue Gelato Strain</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/blueberry-muffin-strain/" rel="dofollow">Blueberry Muffin Strain</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/bubblegum-popperz-strain/" rel="dofollow">Bubblegum Popperz Strain</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/gary-payton-strain/" rel="dofollow">Gary Payton Strain</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/hella-jelly-strain/" rel="dofollow">Hella Jelly Strain</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/kosher-kush-strain/" rel="dofollow">Kosher Kush Strain</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/lava-cake-strain/" rel="dofollow">Lava Cake Strain</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/miracle-alien-cookies-strain/" rel="dofollow">Miracle Alien Cookies Strain</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/moonrock-pre-roll/" rel="dofollow">Moonrock Pre Roll</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/og-kush/" rel="dofollow">OG Kush</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/tropical-runtz-strain/" rel="dofollow">Tropical runtz strain</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/watermelon-runtz-strain/" rel="dofollow">Watermelon Runtz Strain</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/backpackboyz-cart/" rel="dofollow">Backpackboyz Cart</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/baked-bar-disposable/" rel="dofollow">Baked Bar Disposable</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/cali-plug-disposable-vape/" rel="dofollow">Cali Plug Disposable Vape</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/clean-carts-2g-disposable/" rel="dofollow">Clean Carts 2G Disposable</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/d9-distillate/" rel="dofollow">D9 Distillate</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/elites-switch-1g-disposable/" rel="dofollow">Elites Switch 1g Disposable</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/expensive-shit-1g-vape/" rel="dofollow">Expensive Shit 1g Vape</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/fryd-donuts-disposable-2g/" rel="dofollow">Fryd Donuts Disposable (2g)</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/gassed-up-2g-disposable/" rel="dofollow">Gassed Up 2g Disposable</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/jungle-boys-vape/" rel="dofollow">Jungle Boys Vape</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/kushy-punch-disposable/" rel="dofollow">Kushy Punch Disposable</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/melt-x-packwoods/" rel="dofollow">Melt X Packwoods</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/packspod-vape/" rel="dofollow">Packspod Vape</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/the-cali-company-disposable-vape/" rel="dofollow">The Cali company disposable vape</a>

<ahref="https://hashclinicc.com/product/tyson-pod-1000mg/" rel="dofollow">Tyson Pod 1000mg</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/buy-the-10-10-boys-2g-disposable-online/" rel "dofollow">Buy THE 10/10 BOYS 2G DISPOSABLE online</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/buy-co2-extract-oil-online/" rel "dofollow">Buy CO2 Extract Oil Online</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/buy-deep-sleep-thc-tincture-online/" rel "dofollow">Buy Deep Sleep THC Tincture Online</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/buy-thc-mood-magic-tincture-online/" rel "dofollow">Buy THC Mood Magic Tincture online</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/buy-atlrx-delta-8-thc-online/" rel "dofollow">Buy ATLRx Delta 8 THC Online</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/buy-revival-watermelon-thc-tincture-online/" rel "dofollow">Buy Revival Watermelon THC Tincture online</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/buy-diamond-extracts-thc-tinctures-online/" rel "dofollow">Buy Diamond Extracts THC Tinctures Online</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/thc-p-vape-cartridge/" rel "dofollow">THC-P Vape Cartridge</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/thca-disposable-2-gram-gourmet-desserts/" rel "dofollow">THCA Disposable 2 Gram – Gourmet Desserts</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/blazed-7-gram-thca-delta-9b-disposable-vape/" rel "dofollow">Blazed 7 Gram THCA + Delta 9B Disposable Vape</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/7-gram-thca-high-thc-p-disposable-vape-limited-series/" rel "dofollow">7 Gram THCA + High THC-P Disposable Vape – Limited Series</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/knockout-blend-live-resin-disposable-2-gram/" rel "dofollow">Knockout Blend Live Resin Disposable – 2 Gram</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/phc-disposable-vape-2-gram/" rel "dofollow">PHC Disposable Vape – 2 Gram</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/hhc-disposable-vape-2-gram-tre-house/" rel "dofollow">HHC Disposable Vape 2 Gram – TRE House</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/live-resin-hhc-p-disposable-vape-delta-extrax/" rel "dofollow">Live Resin HHC-P Disposable Vape – Delta Extrax</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/thc-jd-3-gram-disposable-thins-delta-extrax/" rel "dofollow">THC-JD 3 Gram Disposable Thins – Delta Extrax</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/thca-delta-9p-3-gram-disposable-blazed/" rel "dofollow">THCA + Delta 9P 3 Gram Disposable – Blazed</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/5-gram-thca-thcm-disposable-vape-exclusive-series/" rel "dofollow">5 Gram THCA + THCM Disposable Vape – Exclusive Series</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/?post_type=product&p=519&preview=true" rel "dofollow">2 Gram THCA Disposable Vapes – Live Rosin</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/thca-vape-cartridge-exotic-kush-live-rosin/" rel "dofollow">THCA Vape Cartridge Exotic Kush – Live Rosin</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/1-gram-thca-disposable-vapes-live-rosin/" rel "dofollow">1 Gram THCA Disposable Vapes – Live Rosin</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/2g-thca-disposable-vapes-minnesota-fire/" rel "dofollow">2G THCA Disposable Vapes – Minnesota Fire</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/thc-vape-juice-wedding-cake/" rel "dofollow">THC Vape Juice Wedding Cake</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/buy-urb-disposable-vape/" rel "dofollow">Buy URB Disposable vape</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/buy-xtra-disposables-vape-online/" rel "dofollow">Buy Xtra Disposables vape online</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/buy-runtz-disposable-vape-pen/" rel "dofollow">Buy RUNTZ DISPOSABLE VAPE PEN</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/buy-dmt-vape-pens/" rel "dofollow">buy Dmt Vape Pens</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/rainbows-and-cherries-live-budder/" rel "dofollow">Rainbows and Cherries Live Budder</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/2-5g-citrus-mac-live-budder/" rel "dofollow">2.5g Citrus MAC Live Budder</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/1g-peking-duck-live-sugar/" rel "dofollow">1g Peking Duck Live Sugar</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/30ml-rest-15-tincture/" rel "dofollow">30ml Rest 1:5 Tincture</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/1g-face-mints-liquid-live-resin-cartridge/" rel "dofollow">1g Face Mints Liquid Live Resin Cartridge</a>

<ahref="https://vapestorecart.com/product/acitivated-thc-distillate-strike-gold/" rel="dofollow">Activated THC distillate Strike gold</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/good-trip-mushroom-chocolate-bars/" rel="dofollow">Good Trip Chocolate Bars</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/fusion-mushroom-chocolate-bars/" rel="dofollow">Fusion Mushroom Chocolate Bars</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/lsd-acid/" rel="dofollow">Lsd (acid)</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/lsd-gel/" rel="dofollow">Lsd Gel Tabs</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/lsd-sheets/" rel="dofollow">LSD SHEETS</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/lsd/" rel="dofollow">Lsd</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/green-hulk-250mg-mdma/" rel="dofollow">Green Hulk (MDMA)</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/white-yellow-technogym/" rel="dofollow">White & Yellow Technogym</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/orange-sprite-mdma/" rel="dofollow">Orange Sprite MDMA Pills</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/red-bull-258mg-mdma/" rel="dofollow">Red Bull Pills (MDMA)</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/orange-trump-260mg-mdma/" rel="dofollow">Orange Trump 260mg MDMA</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/one-up-mushroom-chocolate-bars/" rel="dofollow">One Up Mushroom Chocolate Bars</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/one-up-raspberry-dark-chocolate-shroom-bars/" rel="dofollow">One Up Raspberry Dark Shroom Chocolate Bars</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/one-up-tagalongs-mushroom-bars/" rel="dofollow">One Up Tagalongs Mushroom Bars</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/one-up-multiverse-vanilla-biscuit/" rel="dofollow"></a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/one-up-multiverse-vanilla-biscuit/" rel="dofollow">One up Multiverse Vanilla Biscuit</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/one-up-mushroom-bars-cookies-and-cream/" rel="dofollow">One Up Psilocybin Mushroom Cookies and Cream</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/one-up-mushroom-bars-do-si-dos/" rel="dofollow">One Up Do-Si-Dos Mushroom Bars</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/one-up-samoas-mushroom-bar/" rel="dofollow">One Up Samoas Mushroom Bar</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/one-up-strawberries-and-cream-mushroom-bars/" rel="dofollow">One Up Strawberries and Cream Mushroom Bars</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/one-up-thin-mints-mushroom-bars/" rel="dofollow">One Up Thin Mints Mushroom Bars</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/one-up-multiverse-almond-crush-chocolate-bar/" rel="dofollow">One Up Multiverse Almond Crush Chocolate Bar</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/one-up-multiverse-blueberry-yogurt/" rel="dofollow">One Up Multiverse Blueberry Yogurt</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/one-up-multiverse-oreo-milkshake/" rel="dofollow">One up Multiverse Oreo Milkshake</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/one-up-multiverse-matcha-milk-tea/" rel="dofollow">One up Multiverse Matcha Milk Tea</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/one-up-multiverse-strawberry-shortcake/" rel="dofollow">One up Multiverse Strawberry Shortcake</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/one-up-psychedelic-chocolate-bar/" rel="dofollow">One Up Psilocybin Chocolate Bar</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/one-up-trefoils-mushroom-bars/" rel="dofollow">One Up Trefoils Mushroom Bars</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/filthy-laboratory/" rel="dofollow">FILTHY LABORATORY</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/flavrx-cartridge/" rel="dofollow">FlavRX Cartridge</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/chronopoly-carts/" rel="dofollow">Chronopoly Carts</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/big-chief-extracts/" rel="dofollow">Big chief extracts</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/exxus-snap/" rel="dofollow">Exxus Snap</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/stiiizys-starter-kit/" rel="dofollow">Stiiizy Disposable</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/exotic-carts/" rel="dofollow">EXOTIC CARTS</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/brass-knuckles-cartridges/" rel="dofollow">Brass Knuckles Cartridges</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/5-me0-dmt/" rel="dofollow">5-Me0-DMT</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/albino-penis-envy-grow-kits/" rel="dofollow">albino penis envy grow kits</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/blue-oyster-mushrooms/" rel="dofollow">blue Oyster Mushroom</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/lions-mane/" rel="dofollow">Lion’s Mane</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/dmt/" rel="dofollow">DMT</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/ecstasy-molly/" rel="dofollow">Ecstasy Pills</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/dmt-vape-pen-and-cartridges/" rel="dofollow">DMT VAPE PEN</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/5-meo-dmt/" rel="dofollow">5-MeO DMT</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/lsd-liquid/" rel="dofollow">Liquid LSD</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/gel-tabs-lsd-300ug/" rel="dofollow">Gel tabs lsd</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/lsd-tabs-250ug/" rel="dofollow">LSD Tabs</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/mdma-crystal/" rel="dofollow">MDMA Crystal</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/psilocybe-azurescens-dried-shrooms/" rel="dofollow">Psilocybe Azurescens mushrooms</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/golden-teacher-mushrooms/" rel="dofollow">Golden Teacher Mushrooms</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/true-albino-teacher-mushroom/" rel="dofollow">True Albino Teacher</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/psilocybe-cyanescens-dried-shrooms/" rel="dofollow">Psilocybe Cyanescens</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/penis-envy/" rel="dofollow">Penis Envy</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/great-white-monster-psilocybe-cubensis/" rel="dofollow">Great White Monster-Psilocybe Cubensis</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/big-daddy-psilocybe-cubensis/" rel="dofollow">Big Daddy Psilocybe Cubensis</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/avery-albino-magic-mushroom/" rel="dofollow">Avery Albino Magic Mushroom</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/albino-cambodians-psilocybe-cubensis/" rel="dofollow">Albino Cambodians Psilocybe Cubensis</a>

<ahref="https://psychedelictripgateway.com/product/albino-a-magic-mushroom-dried-shrooms/" rel="dofollow">Albino A+ Magic Mushroom</a>

Not to trip but to help improve mental health/self esteem and also give relief from issues

like BPD,panic attacks,chronic pains,Bipolar,PTSD,ADHD,depression,anxiety and other mental disorders.

And also if you want very high trip, we can recomment for all beginners.buy penis envy mushrooms.

for your orders just click and safe the stress we ship and do delivery to all locations.

https://annarborshroom.com/product/mushroom-chocolate-bars-near-me

https://annarborshroom.com/product/mushroom-chocolate-bars

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/"rel="external">arbor shrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/polkadot-dragonfruit-near-me/"

rel="external">polka dot chocolate</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-berries-cream/"

rel="external">polka dot berries cream</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-chocolate-cherrios/"

rel="external">polka dot mushroom</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-chocolate-coconut/"

rel="external">polka dot chocolate coconut</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/magic-mushroom-chocolate-bars/"

rel="external">mushroom chocolate bars</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-polkadot-blueberry-muffin/"

rel="external">chocolate bars</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-polkadot-magic-mushroom/"

rel="external">polka dot chocolate bars</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/blue-meanies-mushroom/"

rel="external">arbor shrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-albino-louisiana-magic-mushrooms-online/"

rel="external">Online Shrooms Dispensary</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/golden-mammoth-mushroom/"

rel="external">golden mammoth mushroom</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-escondido-magic-mushrooms-online/"

rel="external">buy escondido-magic online</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-dancing-tiger-magic-mushrooms/"

rel="external">buy dancing tiger magic mushrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-daddy-long-legs-magic-mushrooms/"

rel="external">buy-daddy long legs magic mushrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/shrooms-edibles-for-sale-psilocybin-mushroom-edibles/"

rel="external">shrooms edibles</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-psilocybin-shrooms-in-ann-arbor/"

rel="external">buy psilocybin shrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-mushroom-psilocybin-capsules-online/"

rel="external">psilocybin capsules online</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/magic-truffles-for-sale-online-usa/"

rel="external">magic truffles for sale</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/magic-mushroom-grow-kits/"

rel="external">magic mushroom grow kits</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/"

rel="external">buy adaptogen blend alignment online</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-ceremonial-blend-the-journey-online/"

rel="external">magic honey</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-100-syrian-rue-the-amplifier-online/"

rel="external">soulcybin</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-100-syrian-rue-the-amplifier-online/"

rel="external">cybin</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/"

rel="external">cybin stock</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/"

rel="external">cybin stock</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/great-white-monster-mushroom/"

rel="external">buy penis envy mushrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-apex-magic-mushrooms-online/"

rel="external">buy apex magic mushrooms online</a>

<a rel="nofollow" href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-apex-magic-mushrooms-online/"

>buy apex magic mushrooms online</a>

<a rel="nofollow" href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/cubes-scooby-snacks-microdose-capsules/"

>cubes-scooby snacks</a>

<a rel="nofollow" href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/cubes-scooby-snacks-50-capsules-vegan/"

>ann arbor mushroom dispensary</a>

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-dmt-vape-online-in-ann-arbor/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/ann-arbor-mushroom-dispensary/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/Mushroom-chocolate-bars/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-albino-louisiana-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/golden-mammoth-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-escondido-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-ecuadorian-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-dancing-tiger-magic-mushrooms/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-daddy-long-legs-magic-mushrooms/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-cuban-magic-mushrooms-michigan/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/where-to-buy-creeper-shroom-usa/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-costa-rican-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/brazilian-magic-mushrooms/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/blue-meanies-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/where-to-buy-blue-magnolia-rust-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/where-to-buy-big-mex-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-b-magic-mushrooms-online-usa/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-averys-albino-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-apex-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/great-white-monster-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/golden-teacher-magic-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-100-syrian-rue-the-amplifier-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-ceremonial-blend-the-journey-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-magic-mushroom-grow-kits/

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/magic-truffles-for-sale-online-usa/

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-mushroom-psilocybin-capsules-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-psilocybin-shrooms-in-ann-arbor/

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/shrooms-edibles-for-sale-psilocybin-mushroom-edibles/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/polkadot-dragonfruit-near-me/

https://annarborshroom.com/2023/10/25/what-are-penis-envy-mushrooms/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-berries-cream/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-chocolate-cherrios/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-chocolate-coconut/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/magic-mushroom-chocolate-bars/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-polkadot-blueberry-muffin/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-polkadot-magic-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/shafaa-macrodosing-magic-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/cordyceps-mushroom-gummies/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/spore-wellness-immune-microdosing-mushroom-capsules/

Not to trip but to help improve mental health/self esteem and also give relief from issues

like BPD,panic attacks,chronic pains,Bipolar,PTSD,ADHD,depression,anxiety and other mental disorders.

And also if you want very high trip, we can recomment for all beginners.buy penis envy mushrooms.

for your orders just click and safe the stress we ship and do delivery to all locations.

https://annarborshroom.com/product/mushroom-chocolate-bars-near-me

https://annarborshroom.com/product/mushroom-chocolate-bars

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/"rel="external">arbor shrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/polkadot-dragonfruit-near-me/"

rel="external">polka dot chocolate</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-berries-cream/"

rel="external">polka dot berries cream</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-chocolate-cherrios/"

rel="external">polka dot mushroom</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-chocolate-coconut/"

rel="external">polka dot chocolate coconut</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/magic-mushroom-chocolate-bars/"

rel="external">mushroom chocolate bars</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-polkadot-blueberry-muffin/"

rel="external">chocolate bars</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-polkadot-magic-mushroom/"

rel="external">polka dot chocolate bars</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/blue-meanies-mushroom/"

rel="external">arbor shrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-albino-louisiana-magic-mushrooms-online/"

rel="external">Online Shrooms Dispensary</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/golden-mammoth-mushroom/"

rel="external">golden mammoth mushroom</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-escondido-magic-mushrooms-online/"

rel="external">buy escondido-magic online</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-dancing-tiger-magic-mushrooms/"

rel="external">buy dancing tiger magic mushrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-daddy-long-legs-magic-mushrooms/"

rel="external">buy-daddy long legs magic mushrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/shrooms-edibles-for-sale-psilocybin-mushroom-edibles/"

rel="external">shrooms edibles</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-psilocybin-shrooms-in-ann-arbor/"

rel="external">buy psilocybin shrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-mushroom-psilocybin-capsules-online/"

rel="external">psilocybin capsules online</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/magic-truffles-for-sale-online-usa/"

rel="external">magic truffles for sale</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/magic-mushroom-grow-kits/"

rel="external">magic mushroom grow kits</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/"

rel="external">buy adaptogen blend alignment online</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-ceremonial-blend-the-journey-online/"

rel="external">magic honey</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-100-syrian-rue-the-amplifier-online/"

rel="external">soulcybin</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-100-syrian-rue-the-amplifier-online/"

rel="external">cybin</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/"

rel="external">cybin stock</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/"

rel="external">cybin stock</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/great-white-monster-mushroom/"

rel="external">buy penis envy mushrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-apex-magic-mushrooms-online/"

rel="external">buy apex magic mushrooms online</a>

<a rel="nofollow" href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-apex-magic-mushrooms-online/"

>buy apex magic mushrooms online</a>

<a rel="nofollow" href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/cubes-scooby-snacks-microdose-capsules/"

>cubes-scooby snacks</a>

<a rel="nofollow" href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/cubes-scooby-snacks-50-capsules-vegan/"

>ann arbor mushroom dispensary</a>

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-dmt-vape-online-in-ann-arbor/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/ann-arbor-mushroom-dispensary/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/Mushroom-chocolate-bars/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-albino-louisiana-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/golden-mammoth-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-escondido-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-ecuadorian-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-dancing-tiger-magic-mushrooms/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-daddy-long-legs-magic-mushrooms/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-cuban-magic-mushrooms-michigan/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/where-to-buy-creeper-shroom-usa/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-costa-rican-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/brazilian-magic-mushrooms/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/blue-meanies-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/where-to-buy-blue-magnolia-rust-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/where-to-buy-big-mex-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-b-magic-mushrooms-online-usa/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-averys-albino-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-apex-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/great-white-monster-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/golden-teacher-magic-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-100-syrian-rue-the-amplifier-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-ceremonial-blend-the-journey-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-magic-mushroom-grow-kits/

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/magic-truffles-for-sale-online-usa/

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-mushroom-psilocybin-capsules-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-psilocybin-shrooms-in-ann-arbor/

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/shrooms-edibles-for-sale-psilocybin-mushroom-edibles/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/polkadot-dragonfruit-near-me/

https://annarborshroom.com/2023/10/25/what-are-penis-envy-mushrooms/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-berries-cream/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-chocolate-cherrios/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-chocolate-coconut/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/magic-mushroom-chocolate-bars/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-polkadot-blueberry-muffin/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-polkadot-magic-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/shafaa-macrodosing-magic-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/cordyceps-mushroom-gummies/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/spore-wellness-immune-microdosing-mushroom-capsules/

Not to trip but to help improve mental health/self esteem and also give relief from issues

like BPD,panic attacks,chronic pains,Bipolar,PTSD,ADHD,depression,anxiety and other mental disorders.

And also if you want very high trip, we can recomment for all beginners.buy penis envy mushrooms.

for your orders just click and safe the stress we ship and do delivery to all locations.

https://annarborshroom.com/product/mushroom-chocolate-bars-near-me

https://annarborshroom.com/product/mushroom-chocolate-bars

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/"rel="external">arbor shrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/polkadot-dragonfruit-near-me/"

rel="external">polka dot chocolate</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-berries-cream/"

rel="external">polka dot berries cream</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-chocolate-cherrios/"

rel="external">polka dot mushroom</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-chocolate-coconut/"

rel="external">polka dot chocolate coconut</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/magic-mushroom-chocolate-bars/"

rel="external">mushroom chocolate bars</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-polkadot-blueberry-muffin/"

rel="external">chocolate bars</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-polkadot-magic-mushroom/"

rel="external">polka dot chocolate bars</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/blue-meanies-mushroom/"

rel="external">arbor shrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-albino-louisiana-magic-mushrooms-online/"

rel="external">Online Shrooms Dispensary</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/golden-mammoth-mushroom/"

rel="external">golden mammoth mushroom</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-escondido-magic-mushrooms-online/"

rel="external">buy escondido-magic online</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-dancing-tiger-magic-mushrooms/"

rel="external">buy dancing tiger magic mushrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-daddy-long-legs-magic-mushrooms/"

rel="external">buy-daddy long legs magic mushrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/shrooms-edibles-for-sale-psilocybin-mushroom-edibles/"

rel="external">shrooms edibles</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-psilocybin-shrooms-in-ann-arbor/"

rel="external">buy psilocybin shrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-mushroom-psilocybin-capsules-online/"

rel="external">psilocybin capsules online</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/magic-truffles-for-sale-online-usa/"

rel="external">magic truffles for sale</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/magic-mushroom-grow-kits/"

rel="external">magic mushroom grow kits</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/"

rel="external">buy adaptogen blend alignment online</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-ceremonial-blend-the-journey-online/"

rel="external">magic honey</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-100-syrian-rue-the-amplifier-online/"

rel="external">soulcybin</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-100-syrian-rue-the-amplifier-online/"

rel="external">cybin</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/"

rel="external">cybin stock</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/"

rel="external">cybin stock</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/great-white-monster-mushroom/"

rel="external">buy penis envy mushrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-apex-magic-mushrooms-online/"

rel="external">buy apex magic mushrooms online</a>

<a rel="nofollow" href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-apex-magic-mushrooms-online/"

>buy apex magic mushrooms online</a>

<a rel="nofollow" href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/cubes-scooby-snacks-microdose-capsules/"

>cubes-scooby snacks</a>

<a rel="nofollow" href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/cubes-scooby-snacks-50-capsules-vegan/"

>ann arbor mushroom dispensary</a>

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-dmt-vape-online-in-ann-arbor/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/ann-arbor-mushroom-dispensary/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/Mushroom-chocolate-bars/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-albino-louisiana-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/golden-mammoth-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-escondido-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-ecuadorian-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-dancing-tiger-magic-mushrooms/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-daddy-long-legs-magic-mushrooms/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-cuban-magic-mushrooms-michigan/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/where-to-buy-creeper-shroom-usa/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-costa-rican-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/brazilian-magic-mushrooms/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/blue-meanies-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/where-to-buy-blue-magnolia-rust-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/where-to-buy-big-mex-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-b-magic-mushrooms-online-usa/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-averys-albino-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-apex-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/great-white-monster-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/golden-teacher-magic-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-100-syrian-rue-the-amplifier-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-ceremonial-blend-the-journey-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-magic-mushroom-grow-kits/

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/magic-truffles-for-sale-online-usa/

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-mushroom-psilocybin-capsules-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-psilocybin-shrooms-in-ann-arbor/

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/shrooms-edibles-for-sale-psilocybin-mushroom-edibles/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/polkadot-dragonfruit-near-me/

https://annarborshroom.com/2023/10/25/what-are-penis-envy-mushrooms/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-berries-cream/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-chocolate-cherrios/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-chocolate-coconut/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/magic-mushroom-chocolate-bars/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-polkadot-blueberry-muffin/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-polkadot-magic-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/shafaa-macrodosing-magic-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/cordyceps-mushroom-gummies/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/spore-wellness-immune-microdosing-mushroom-capsules/

Not to trip but to help improve mental health/self esteem and also give relief from issues

like BPD,panic attacks,chronic pains,Bipolar,PTSD,ADHD,depression,anxiety and other mental disorders.

And also if you want very high trip, we can recomment for all beginners.buy penis envy mushrooms.

for your orders just click and safe the stress we ship and do delivery to all locations.

https://annarborshroom.com/product/mushroom-chocolate-bars-near-me

https://annarborshroom.com/product/mushroom-chocolate-bars

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/"rel="external">arbor shrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/polkadot-dragonfruit-near-me/"

rel="external">polka dot chocolate</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-berries-cream/"

rel="external">polka dot berries cream</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-chocolate-cherrios/"

rel="external">polka dot mushroom</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-chocolate-coconut/"

rel="external">polka dot chocolate coconut</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/magic-mushroom-chocolate-bars/"

rel="external">mushroom chocolate bars</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-polkadot-blueberry-muffin/"

rel="external">chocolate bars</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-polkadot-magic-mushroom/"

rel="external">polka dot chocolate bars</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/blue-meanies-mushroom/"

rel="external">arbor shrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-albino-louisiana-magic-mushrooms-online/"

rel="external">Online Shrooms Dispensary</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/golden-mammoth-mushroom/"

rel="external">golden mammoth mushroom</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-escondido-magic-mushrooms-online/"

rel="external">buy escondido-magic online</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-dancing-tiger-magic-mushrooms/"

rel="external">buy dancing tiger magic mushrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-daddy-long-legs-magic-mushrooms/"

rel="external">buy-daddy long legs magic mushrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/shrooms-edibles-for-sale-psilocybin-mushroom-edibles/"

rel="external">shrooms edibles</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-psilocybin-shrooms-in-ann-arbor/"

rel="external">buy psilocybin shrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-mushroom-psilocybin-capsules-online/"

rel="external">psilocybin capsules online</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/magic-truffles-for-sale-online-usa/"

rel="external">magic truffles for sale</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/magic-mushroom-grow-kits/"

rel="external">magic mushroom grow kits</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/"

rel="external">buy adaptogen blend alignment online</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-ceremonial-blend-the-journey-online/"

rel="external">magic honey</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-100-syrian-rue-the-amplifier-online/"

rel="external">soulcybin</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-100-syrian-rue-the-amplifier-online/"

rel="external">cybin</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/"

rel="external">cybin stock</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/"

rel="external">cybin stock</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/great-white-monster-mushroom/"

rel="external">buy penis envy mushrooms</a>

<a href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-apex-magic-mushrooms-online/"

rel="external">buy apex magic mushrooms online</a>

<a rel="nofollow" href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-apex-magic-mushrooms-online/"

>buy apex magic mushrooms online</a>

<a rel="nofollow" href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/cubes-scooby-snacks-microdose-capsules/"

>cubes-scooby snacks</a>

<a rel="nofollow" href="https://annarborshroom.com/product/cubes-scooby-snacks-50-capsules-vegan/"

>ann arbor mushroom dispensary</a>

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-dmt-vape-online-in-ann-arbor/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/ann-arbor-mushroom-dispensary/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/Mushroom-chocolate-bars/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-albino-louisiana-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/golden-mammoth-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-escondido-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-ecuadorian-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-dancing-tiger-magic-mushrooms/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-daddy-long-legs-magic-mushrooms/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-cuban-magic-mushrooms-michigan/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/where-to-buy-creeper-shroom-usa/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-costa-rican-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/brazilian-magic-mushrooms/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/blue-meanies-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/where-to-buy-blue-magnolia-rust-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/where-to-buy-big-mex-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-b-magic-mushrooms-online-usa/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-averys-albino-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-apex-magic-mushrooms-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/great-white-monster-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/golden-teacher-magic-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-100-syrian-rue-the-amplifier-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-soulcybin-ceremonial-blend-the-journey-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-adaptogen-blend-alignment-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-magic-mushroom-grow-kits/

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/magic-truffles-for-sale-online-usa/

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-mushroom-psilocybin-capsules-online/

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/buy-psilocybin-shrooms-in-ann-arbor/

https://annarborshroom.com/product-category/shrooms-edibles-for-sale-psilocybin-mushroom-edibles/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/polkadot-dragonfruit-near-me/

https://annarborshroom.com/2023/10/25/what-are-penis-envy-mushrooms/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-berries-cream/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-chocolate-cherrios/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/polka-dot-chocolate-coconut/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/magic-mushroom-chocolate-bars/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-polkadot-blueberry-muffin/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/buy-polkadot-magic-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/shafaa-macrodosing-magic-mushroom/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/cordyceps-mushroom-gummies/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/spore-wellness-immune-microdosing-mushroom-capsules/

Find relief from stress, tension, and fatigue. Experience harmony with this shrooms. Are you tired of the

relentless stress,deppression and fatigue in your life? arbor shrooms protection offers a path to relief and balance.

It's your opportunity to escape the chaos and embrace a harmonious existence.

Your journey to well-being.Begins with this buy psilocybin shrooms in ann abor!

https://annarborshroom.com/product/magic-mushroom-chocolate-bars/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/mushroom-chocolate-bars/

Find relief from stress, tension, and fatigue. Experience harmony with this shrooms. Are you tired of the

relentless stress,deppression and fatigue in your life? arbor shrooms protection offers a path to relief and balance.

It's your opportunity to escape the chaos and embrace a harmonious existence.

Your journey to well-being.Begins with this buy psilocybin shrooms in ann abor!

https://annarborshroom.com/product/magic-mushroom-chocolate-bars/

https://annarborshroom.com/product/mushroom-chocolate-bars/

Nice article! Every business needs an importer of record for smooth shipping.

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/jetlato-strain/"rel="dofollow">Jetlato Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/rainbowz/"rel="dofollow">Cadillac Rainbowz Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/alien-labs-live-resin/"rel="dofollow">live resin vs distillate</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/weeding-cake/"rel="dofollow">gelato cake weed strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/zushi/"rel="dofollow">Blue Zushi</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/caramel-cream-%f0%9f%8d%a6/"rel="dofollow">Caramel Cream strain ????</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/triple-chocolate-chip-smalls-%f0%9f%8d%ab/"rel="dofollow">triple chocolate chip strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/unpacked-rosin/"rel="dofollow">Unpacked Rosin</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/hash-house-6/"rel="dofollow">6 Star Hash Rosin</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/fresh-squeeze-rosin/"rel="dofollow">Fresh Squeeze Rosin</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/wca-x-puremelt-rosin/"rel="dofollow">WCA x Puremelt Rosin</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/boutiq-prerolls/"rel="dofollow">Boutiq Prerolls</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/the-standard-hashholes-authenticbaby-jeeters/"rel="dofollow">Baby Jeeters</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/sweet-tarts-%f0%9f%8d%ac/"rel="dofollow">Sweet Tartz Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/white-gruntz/"rel="dofollow">Gruntz Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/candy-popper-%f0%9f%8e%89/"rel="dofollow">candy popper strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/honey-bun-%f0%9f%8d%af-%f0%9f%8d%9e/"rel="dofollow">Honey Bun Weed Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/horchata-%f0%9f%a5%9b/"rel="dofollow">Horchata Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/banana-berry-acai-%f0%9f%8d%8c-%f0%9f%8d%93%f0%9f%ab%90/"rel="dofollow">Banana Berry strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/sundae-zerbert-%f0%9f%8d%a6/"rel="dofollow">white zerbert strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/strawberry-banana-%f0%9f%8d%8c-%f0%9f%8d%93/"rel="dofollow">Strawberry Banana Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/cupcake-smalls-%f0%9f%a7%81/"rel="dofollow">Blueberry Cupcake Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/cereal-milk-smalls-%f0%9f%a5%a3-%f0%9f%a5%9b/"rel="dofollow">Cereal Milk Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/abba-zabba-smalls-%f0%9f%aa%a8/"rel="dofollow">Abba Zabba Smalls Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/glitter-bomb-%f0%9f%92%a3/"rel="dofollow">Glitter Bomb Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/slurricane-smalls-%e2%9b%88%ef%b8%8f/"rel="dofollow">Slurricane Smalls Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/jealousy-runtz-%e2%ad%90/"rel="dofollow">Jealousy Runtz Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/jetlato-crasher-%f0%9f%92%a5/"rel="dofollow">Jetlato Crasher</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/cherry-icee-%f0%9f%8d%92/"rel="dofollow">Cherry ICEE Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/alien-mac-%f0%9f%91%bd/"rel="dofollow">Alien Mac Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/cherry-zourz-%f0%9f%8d%92/"rel="dofollow">Cherry Zourz Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/sunkist-%f0%9f%8d%8a/"rel="dofollow">Sunkist Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/tangyberry-%f0%9f%8d%93/"rel="dofollow">Tangie berry Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/now-later-%f0%9f%8d%ac/"rel="dofollow">Now And Later Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/rocky-road-ice-cream-%f0%9f%8d%a6%f0%9f%aa%a8/"rel="dofollow">Rocky Road Ice Cream Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/trufflez-%f0%9f%8d%ac/"rel="dofollow">Trufflez Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/cherry-crasher-%f0%9f%8d%92/"rel="dofollow">Cherry Crasher Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/ice-cream-sherbert-%f0%9f%8d%a6/"rel="dofollow">Ice-Cream Sherbet Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/chips-ahoy-%f0%9f%8d%aa/"rel="dofollow">Chips Ahoy Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/snickerdoodle/"rel="dofollow">Snickerdoodle Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/mac-1/"rel="dofollow">Mac 1 Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/milk-duds-%f0%9f%8d%bc/"rel="dofollow">Milk Duds Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/product/"rel="dofollow">Slurty Smalls Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/churro-smalls/"rel="dofollow">Churro Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/fryd-2g-disposable-authentic/"rel="dofollow">Fryd 2g Disposables</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/good-2g-disposable-authentic/"rel="dofollow">Good Good 2g Disposable</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/packman-2g-disposable-authentic/"rel="dofollow">Packman 2g Disposable</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/turn-2g-disposable-authentic/"rel="dofollow">Turn 2g Dispo</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/edibles-500mg/"rel="dofollow">500mg Edible</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/pixels-2g-disposable-authentic/"rel="dofollow">Pixels 2g Disposable</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/big-cheif-cartridges/"rel="dofollow">Big Cheif Carts</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/mad-labs-2g-disposable/"rel="dofollow">Mad Labs 2g Disposable</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/trove-2g-disposable/"rel="dofollow">Trove 2g Disposable</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/baked-bar-2g-disposable/"rel="dofollow">Baked Bar 2g Disposable</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/space-club-2g-disposable/"rel="dofollow">Space Club 2g Disposable</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/2470/"rel="dofollow">Blues Brothers Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/captain-jack/"rel="dofollow">Captain Jack Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/nilla-wafers/"rel="dofollow">NILLA WAFERS STRAIN</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/chocolate-hashberry/"rel="dofollow">CHOCOLATE HASHBERRY STRAIN</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/black-diamond-og/"rel="dofollow">BLACK DIAMOND OG</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/do-si-dos/"rel="dofollow">dos si do strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/cherry-pie-2/"rel="dofollow">CHERRY PIE STRAIN</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/the-judge/"rel="dofollow">THE JUDGE STRAIN</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/flav-thc-gummies/"rel="dofollow">Flav THC Gummies</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/buy-live-resin/"rel="dofollow">Buy Live Resin</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/good-high-gummies/"rel="dofollow">Colorful and tempting Sugar High Gummies</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/canna-butter-1000mg-thc/"rel="dofollow">Canna Butter 1000mg THC</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/fruity-pebbles-500mg-cereal-bar/"rel="dofollow">Fruity Pebbles 500mg Cereal Bar</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/gusher-gummies/"rel="dofollow">Gusher Gummies</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/thc-rainbow-belts/"rel="dofollow">THC Rainbow Belts</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/gumbo-bluto/"rel="dofollow">Bluto Gumbo</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/flamin-hot-cheetos-edible-600mg-thc-pot-chips/"rel="dofollow">Edible Hot Cheetos</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/420-pot-heads-500mg-edible/"rel="dofollow">420 Pot Heads 500mg Edible</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/peach-rings-edibles/"rel="dofollow">Peach Ring Edibles</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/sour-apple-bites/"rel="dofollow">Sour Apple BitesSour Apple Bites</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/gummy-worms/"rel="dofollow">Sour Gummy Worms</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/skittles/"rel="dofollow">Skittlez</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/trips-ahoy-cookies/"rel="dofollow">Trips Ahoy Cookies</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/dior-gumbo/"rel="dofollow">Dior Gumbo Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/villain-gumbo/"rel="dofollow">Villain Gumbo</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/gumbo-strain/"rel="dofollow">Gumbo Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/dior-gumbo/"rel="dofollow">Dior Gumbo Strain</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/blueprint-gumbo-2/"rel="dofollow">Blueprint Gumbo</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/up-town-gumbo/"rel="dofollow">Up Town gumbo</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/cheese-cannabis-oil-vape-cartridge-2/"rel="dofollow">CBD Vape Oil Cartridge</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/candyland-dankvapes-2/"rel="dofollow">CANDYLAND DANKVAPES</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/buy-heavy-hitters-cartridge-2/"rel="dofollow">Heavy Hitters Cartridge</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/brass-knuckles-vape-cartridge-2/"rel="dofollow">BRASS KNUCKLES VAPE</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/buy-bloomvape-cartridges-2/"rel="dofollow">BUY BLOOMVAPE CARTRIDGES</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/blackberry-kush-vape-cartridge-500mg-2/"rel="dofollow">Blackberry Kush Vape Cartridge</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/bhang-naturals-hybrid-cartridges-2/"rel="dofollow">Bhang Cartridge</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/therapeutic-treats-raspberries-cinnamon-cbd-chocolate-60mg-bar/"rel="dofollow">Cinnamon CBD Chocolate Bar</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/blueprint-gumbo/"rel="dofollow">Blueprint Gumbo</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/buy-villain-gumbo/"rel="dofollow">Villain gumbo</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/buy-up-town-gumbo-online/"rel="dofollow">Buy UpTown Gumbo</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/ace-of-spades-dank-vapes-2/"rel="dofollow">ACE OF SPADES DANK VAPES</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/ak-47-dankvapes-2/"rel="dofollow">AK-47 DANK VAPES</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/ancient-og-dankvapes-2/"rel="dofollow">ANCIENT OG DANK VAPES</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/237-express-gumbo/"rel="dofollow">237 Express Gumbo</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/flo-wax-vape-pen-2/"rel="dofollow">FLO Wax Vape Pen</a>

<a href="https://calibudonlinestore.com/product/neurogan-cbd-cookies/"rel="dofollow">Neurogan CBD Cookies</a>